Skip to section

WRITING ENCOUNTERS

Welcome to the University Writing Program’s page for Writing Encounters, the bi-semester performance series that stages those special experiences had with the world of symbols and abstraction.

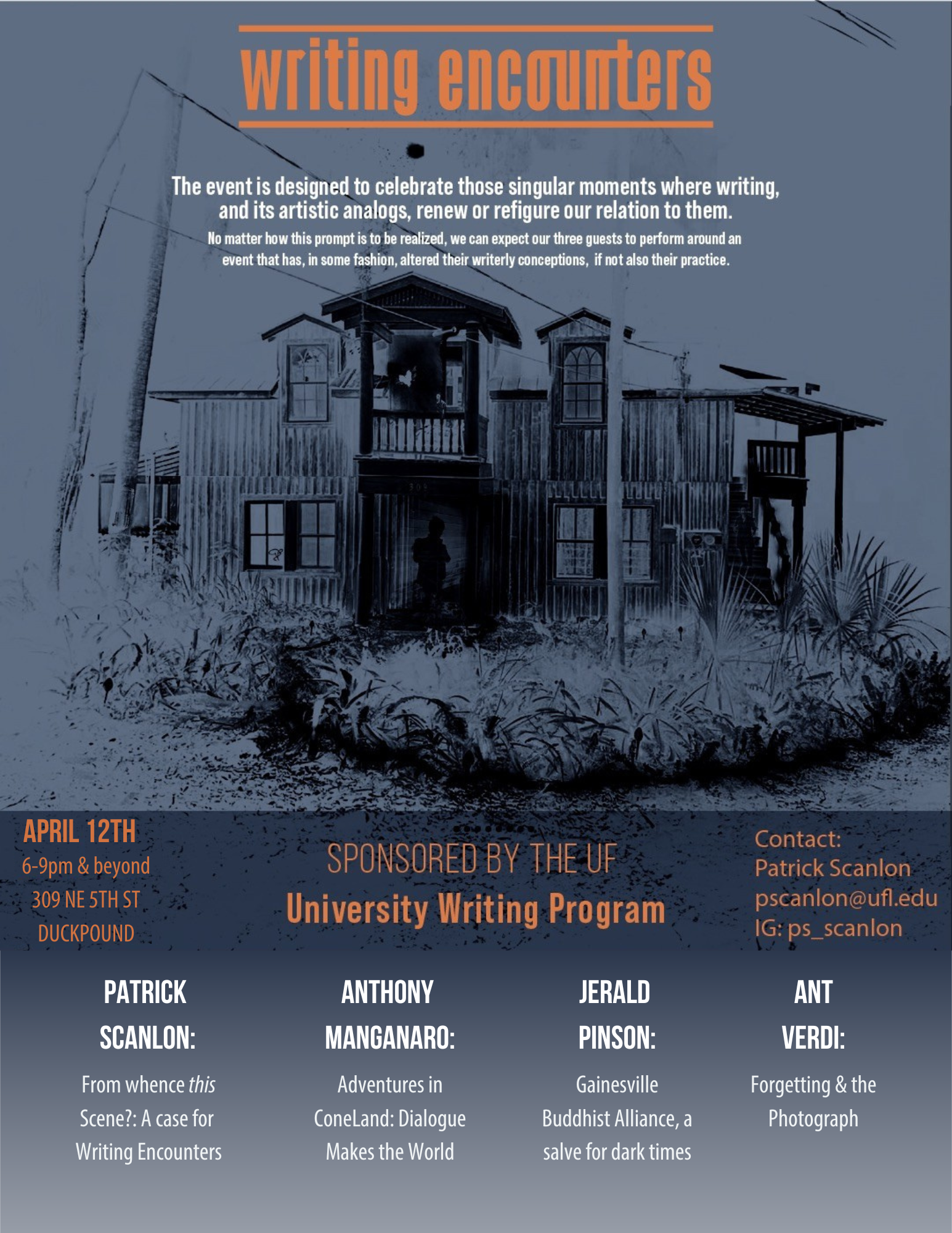

Our event is designed to celebrate those singular moments where writing, and its artistic analogs, renew or refigure our relation to them. No matter how this prompt is to be realized, we can expect the night’s three guests to write, read, speak and perform around an event that has, in some fashion, altered their writerly conceptions, if not also their practice. One might share a piece about such a scene, or present an older piece which is, in turn, framed accordingly. The work can be about reading or language or teaching or painting, etc. One might even choose to read another’s work, and present this encounter as the epiphanic one. Regardless of format, what you provide can be, in the most certain terms, casual and cursory.

On this page you will find—with the formal invitation (past & current one)—a more thorough description of the event and call for presentations, as well as contact information should any queries arise about opportunities to participate. There is a myriad of ways to assist, and we not only welcome the help but hope to engender as much cooperation and communal contribution as possible.

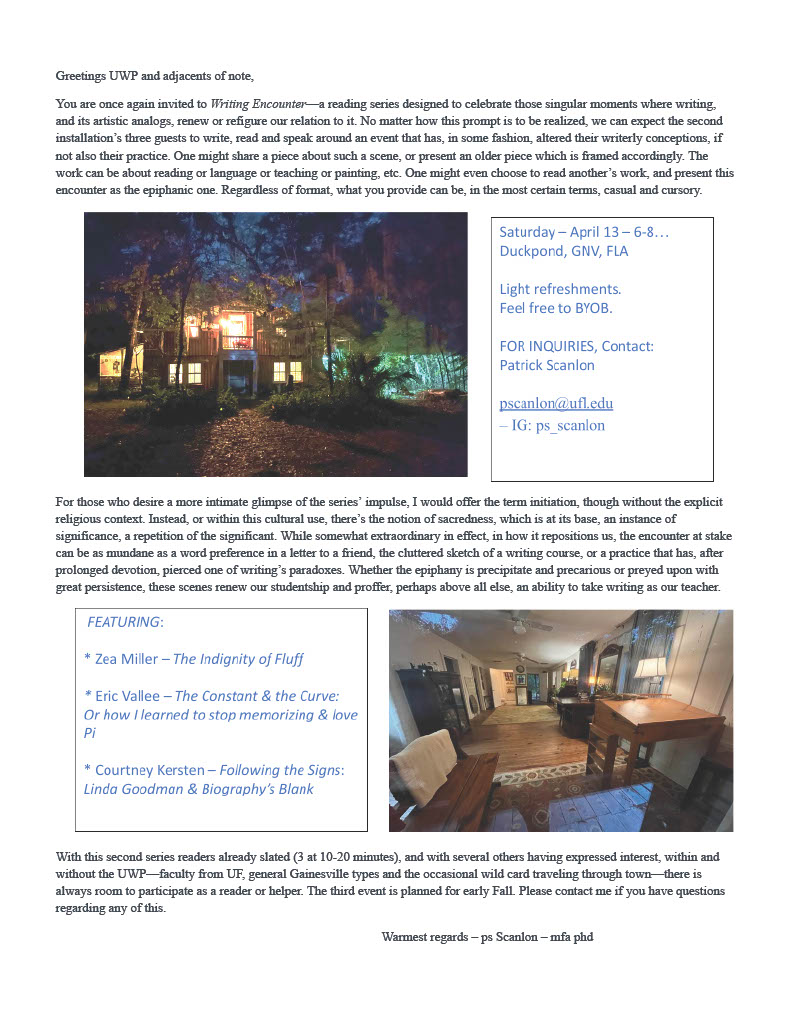

There is an assortment of pics and video clips from the inaugural event (1/20/24), which will be updated as content filters in. My apologies for the somewhat shoddy nature of the recordings—their incompleteness and shaky display—they were a bit spontaneous. We hope to improve our archival abilities with each session.

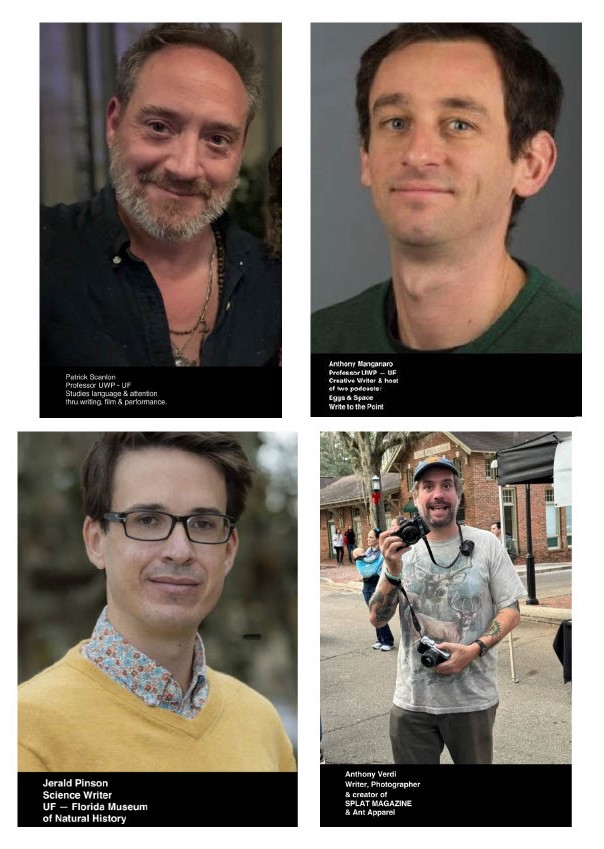

I would like to extend a huge thanks to those within the UWP and the GNV that made this happen: In particular Darby Wood Walters, Anton Matytsin, Austin Deely, Yukai Chen, Mary Beth Aldridge, and of course our presenters: Zea Miller, Eric Valee, Courtney Kersten, Darby Wood Walters, Andréa Caloiaro and Creed Greer. This page will continue to be updated as more footage, description and writing gets processed. For its construction and maintenance, a huge thanks to the UWP’s own Julianna Panton and the Academic Assistant.

WRITING ENCOUNTERS 2 : APRIL 12, 2024

ZEA MILLER – THE INDIGNITY OF FLUFF

The Indignity of Fluff (Excerpt)

Whatever was happening was strange, but I felt like I belonged here, among all the other pillows. It was right somehow. Erin went back into the fray. I made sure to protect her. I don’t know why she kept putting herself into this fight. There were better ways to spend time with me.

Her aggression soon began taking its toll. I felt the fibers surrounding my zipper becoming looser. The side opposite her hands suffered absolute numbness. It didn’t seem right anymore. I would prefer laying on a bed to this.

I collided with another pillow, but I didn’t push back. I don’t think I could have anyway. For a second, I thought it spoke to me. I didn’t understand. I couldn’t believe it. Was there really another one out there?

ERIC VALLEE – THE CONSTANT & THE CURVE: OR HOW I LEARNED TO STOP MEMORIZING & LOVE PI

COURTNEY KERSTEN – FOLLOWING THE SIGNS: LINDA GOODMAN & BIOGRAPHY’S BLANK

VISUAL COMPONENT – PATRICK SCANLON: SURFACE COPERNICUS

Surface Copernicus (9 min), a collaboration with Kyle Corea and Stone Dow, involves the projection of four super 8 films simultaneously, though displayed separately as the four quadrants of a larger square,. Each quadrant represents one of the primary figures of the Copernican Revolution: Nicholas Copernicus; Johannes Kepler; Galileo Galilei; and Isaac Newton. Their specific films are comprised from the qualities, movements and meanings associated with each person, and their work – while a select textual sampling of their theories are embedded in the films, visually and through a voice narration.

This expanded cinema piece combines the pulsating shapes and colors of the visual component, buoyant and tidal, with a musical composition developed according to the principles — mathematical, geometrical, natural — of the early astronomers and their predecessors (designed by Clint Hartzell).

As much as retrieving repressed histories, these films explore the advantage of employing poetic methods in a research endeavor: ones that are interpretive and strange, qualities that respect the complexity of any cultural “event,” and honor the possibility for reorganizing the present. Our intuition and intention is presented in these films, however humbly, through a set of devices quite similar to those of the medieval adepts: glass lenses, a catalogue of lights, numerical calculations, and frequencies maneuvering under an unmanageable darkness.

The texts shown in the film are all first editions, care of Columbia University’s Rare Books and Manuscript Library. A version of this work was performed at MONO NO AWARE VIII, 2014

INAUGURAL EVENT: WRITING ENCOUNTERS 1: JAN. 20, 2023

DARBY WOOD WALTERS – THE WHITE WHALE: POEMS FOR MOBY DICK

* Apologies to Darby Wood Walters for the lack of footage. The talk was so moving I forgot to record. Fortunately, she was gracious enough to include some of her fantastic piece.

The White Whale: A Memoir (Excerpts)

“Did you ever read Moby Dick, daddy?”

His watery gaze expanded for a moment until it found my own. “My name is Ishmael!” he cried with a one-armed flourish and his gaze narrowed once again to NCIS.

Close enough.

My father was born one hundred and ten days before the stock market crashed in 1929. What followed was a damper and drizzlier November than the American soul had envisioned in a long time. My grandfather lost his farm and his temper at approximately the same moment and left dad with toddler memories of a consuming hunger and a dislocated shoulder. In the heart of the dust bowl, there was no ocean to retreat to.

What would have happened if Ishmael had not found his whaling boat? Would he have resorted to the “pistol and ball” as he claimed? Or would he stand with the miles of landsman, staring off into the watery distance until the mold and moss of the humid shore covered his bones with growths just as formidable as the barnacles on the great sperm whale? Or would he have simply continued – teaching glassy eyed students their multiplication tables – because, really, what else do you do?

Dad’s parents seemed to anticipate the upcoming deprivations when they named him. H T. Dad claims that his mother was inspired by the local Native American tribe who named their children the first thing they saw after giving birth. He says his mother had decided to name him, her only son, after the first thing she heard. “Hold This,” he concludes with a smile. That’s what the doctor had allegedly said as he handed him over. It wasn’t until I was in my teens that I learned the real story. He was named in honor of his father: Henry Thomas.

Melville’s son kept a pistol underneath his pillow every night until he killed himself with it. What made that teenager pull the trigger? Four days after his son’s birth, Herman wrote: “He’s a perfect prodigy… I think of calling him Barbarossa—Adolphus—Ferdinand… Granissimo—Hercules—Sampson—Bonaparte.” But instead he called him Malcom.

Eventually, unlike his father, dad’s thoughts did turn to vast expanses. “A fighter pilot!” he declares triumphantly. “I wanted to swoop down out of the sky onto the unsuspecting Japs!” Of course, by the time he could act on his desires, it was the Koreans that America’s pitiless gaze had turned towards. In the end, it didn’t matter. The inch thick glasses he wore kept him out of the pilot’s seat and out of the skies. The air force still took him, though. “I was two standard deviations above the mean on any test they could give me,” he recites, “I could fix any damn electronic they could throw at me.”

Part 6: Disintegration

A couple of weeks ago, I went out to lunch with my parents while I was home for Thanksgiving . My mother and I sat and watched dad eat a hamburger. It came restaurant style, with both buns facing up – patty and cheese on one side, lettuce and tomato on the other. Dad unzipped his brand new black USC jacket and carefully tucked each side away from his considerable stomach, picked up the bare patty and piled it with potato chips lettuce, tomato, and cheese. “Do you want any ketchup?” mom asked. “No, sweety, thank you,” he said and swept the booth with his smile. Of course, when he picked up the patty, it began to disintegrate in his hands. “This burger’s awfully tricky,” he mumbled. “You think they could at least give you some damn, ketchup.” “I’ll go get you some,” said mom. He only made it half way through; the other pieces fell down the side of his jacket and onto the floor.

Ishmael understood the importance of breaking things down into their component parts. He spent ten chapters in synecdochic exploration of the body of the whale. And from the trussing of the whale to the ship, to the storing of the sperm, we learn each step that reduces the leviathan to a candle. Yet, each part is a process that can be further elaborated. To burn the fat, one must first light a fire; to light a fire, one must first strike a match; to strike a match, one must first open the match box; to open the match box, one must first stick out one’s finger or thumb. I wonder if, as each process breaks down, simply breathing becomes the subject of whole novels.

We first noticed something new was wrong when we kept finding the weapons. Sleeping with a revolver under the pillow led to keeping mace by the bedside, which was followed by a baseball bat hidden behind the set of drawers. The crowning touch was a full-sized bow and arrow replete with “bone penetrating” arrow tips innocuously leaning in the corner of the room. “Somebody was on our deck last night,” dad says, “I went outside and I could see their footprints.”

In the 1851 British edition of Moby Dick, the editors omitted the epilogue. The reviewers reviled the book, which appeared to be told by a narrator who had already drowned.

Mom called me a couple of days ago to report that dad had fallen again. “It was actually kind of funny, if you think about it in the right way,” she said, “If you ignored the little smears of blood, he looked just like a little whale lying there on the floor next to the bed, with his big white Depends on. He was good about it and after I got him up, we even laughed a little.”

What if Ishmael had drowned out there in the Pequod’s vortex? Would Moby Dick cease to exist? Would it just be a shitty book that didn’t make any sense? Would apologists postulate a rescued diary, thrown to safety just before the end? Does it really matter?

“I’m not afraid to die,” dad says, “but I wish I knew what it meant. All that knowledge, experience, memory – do you think it just drains out all at once? Like the water draining out of a bathtub?”

ANDRÉA CALOIARO – WHAT DID BACH REALLY PLAY? IMPROVISATION: THE WRITER AS CO-COMPOSER

CREED GREER – LUNCH WITH DERRIDA

HOUSE REPLY : MICKEY SCHAFER

Current Invitation